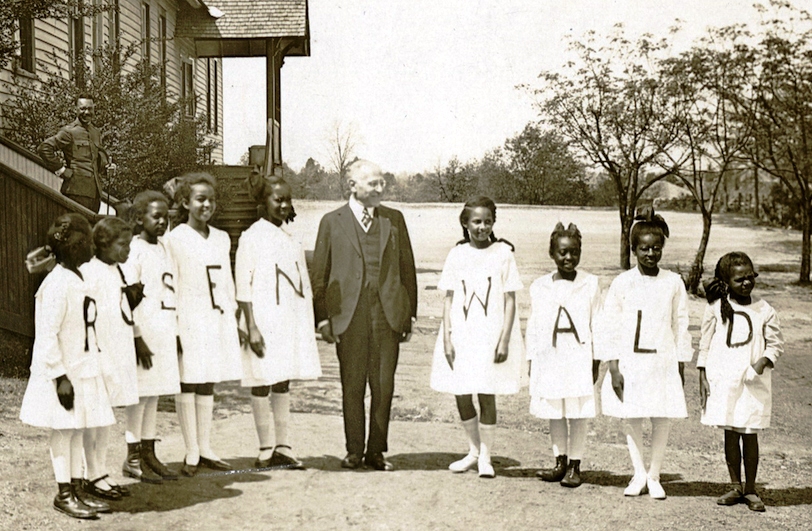

New film, ‘Rosenwald,’ tells story of Jewish philanthropist who transformed black lives

FILM REVIEW

By Lisa Hostein - JTA

Alex Bethea, the son of cotton and tobacco farm workers, was in sixth grade in 1965 when his family moved from Dillon, South Carolina, to the tiny town of Fairmont, North Carolina, where he attended a school called Rosenwald.

But it wasn’t until this week, 50 years later, that Bethea learned that his school was named for Julius Rosenwald, the Jewish philanthropist who is the subject of a new documentary by Aviva Kempner. The film tells the little-known story of Rosenwald’s contribution to African-American culture and education.

The revelation came at a July 14 session at the national convention of the NAACP, which drew several thousand delegates to Philadelphia. Bethea was one of some 70 people who attended a screening of the film, “Rosenwald.”

“Julius Rosenwald had a great impact on my life, and I didn’t even know it,” said Bethea, now a vice principal at an elementary school in New Jersey. “This helps me put the pieces of the puzzle of my life together.”

The philanthropy Rosenwald invested in African-American causes in the early 1900s changed the course of education for thousands of children in the rural South and helped foster the careers of prominent artists, including writer Langston Hughes, opera singer Marion Anderson and painter Jacob Lawrence.

Rosenwald, who made his fortune at the helm of Sears, Roebuck and Co., also provided seed money to build YMCAs for blacks in cities around the country. In addition, he developed a huge apartment complex in Chicago to help improve the living conditions for the masses who had migrated from the Jim Crow South.

“It’s a wonderful story of cooperation between this philanthropist who did not have to care about black people, but who did, and who expended his considerable wealth in ensuring that they got their fair shake in America,” Julian Bond, the renowned civil rights leader, says in the documentary.

Kempner told JTA that her new film on Rosenwald “celebrates the affinity between African-Americans and Jews” that started long before the civil rights movement and speaks to the powerful Jewish tradition of tikkun olam, or repairing the world.

Kempner joined Bond and Rabbi David Saperstein, the former head of the Reform movement’s Religious Action Center who now serves as U.S. ambassador at large for International Religious Freedom, for a discussion after the screening at the NAACP conference. It was while attending a public program 12 years ago on Martha’s Vineyard at which Bond and Saperstein discussed black-Jewish relations that Kempner first learned of Rosenwald’s work with African-Americans.

She calls this film the last of a trilogy documenting the lives of “under-known Jewish heroes.” The first two were about baseball legend Hank Greenberg and radio and TV personality Gertrude Berg.

Interspersing archival footage with interviews with prominent African-Americans like Maya Angelou and U.S. Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.), both of whom attended Rosenwald schools, the documentary tracks the ascent of Rosenwald, the son of German immigrants who rose to become one of the most powerful businessmen and philanthropists in early 20th-century America.

His father, Sam, who came to America in 1851, began, like so many Jewish immigrants of his time, as a peddler. He eventually settled in Springfield, Illinois, where Julius grew up across the street from Abraham Lincoln’s home.

In 1878, his parents sent the 16-year-old Julius to New York to apprentice with his uncles in the men’s clothing manufacturing business. He returned to Illinois to start his own manufacturing company, and through some business and family connections ultimately partnered with Richard Sears, one of the founders of Sears, Roebuck and Co. After Rosenwald took over the company in 1908, it became the largest retailer in the country.

Alex Bethea, a city councilman in Trenton, N.J., who participated in the NAACP convention, attended a Rosenwald school in North Carolina. (Lisa Hostein)

Outside his business life, Rosenwald was heavily influenced by his rabbi, Emil Hirsch, the spiritual leader of the Chicago Sinai Congregation, and he became a major benefactor of Jewish causes.

The film’s historians document the parallels Rosenwald drew at the time between the pogroms against European Jews and violent attacks on blacks in America. He was particularly moved by the race riots in 1908 in Springfield, which are said to have sparked the founding of the NAACP. Hirsch was one of the original leaders of the NAACP, and Rosenwald sponsored its first meetings at his temple.

He was also influenced by the writings of Booker T. Washington, a prominent black leader at the time, and became a funder of Washington’s Tuskegee University in Alabama.

When Rosenwald gave a $25,000 gift to Tuskegee, Washington suggested taking a few thousand dollars to build six schools for young children. Until then, most black children didn’t attend school, but instead spent their time working in the fields alongside their parents. The few schools that did exist were primitive shacks staffed mostly by untrained teachers.

Rather than donating all the money for the schools, Rosenwald gave one-third of the funds needed and challenged the local black community to raise another third and the local white community to contribute the rest. In the end, some 5,300 schools were built with seed money from the Rosenwald Fund.

The fund soon switched focus and began supporting promising black artists, helping catapult dozens onto the national stage.

The Rosenwald Fund “was the single-most important funding agency for African- American culture in the 20th century,” poet Rita Dove says in the film.

Kempner calls Rosenwald one of the greatest examplars of American Jewish philanthropy and says she hopes her film – whose official opening in theaters is scheduled for mid-August — will motivate others to continue that tradition.

“Not all of us can be Julius Rosenwald,” she said, noting that he gave away a total of $62 million in his lifetime, but “we can all do something.”