Divided we stand

In a Thanksgiving Tweet, I remarked lightly that I’d “heard my first official ‘It's-only-Thanksgiving-and-Christmas-is-still-five-weeks-away’ Christmas song at 8 a.m. this morning. In a kosher bakery in Brookline.” Then I added: “As #ThomasJefferson said about religion in America: ‘Divided we stand.’”

A reader wrote to ask if I was being facetious or making some obscure Jefferson joke. Far from it, I answered, and provided a link so she could read Jefferson’s original comment. I want to expand on the point here.

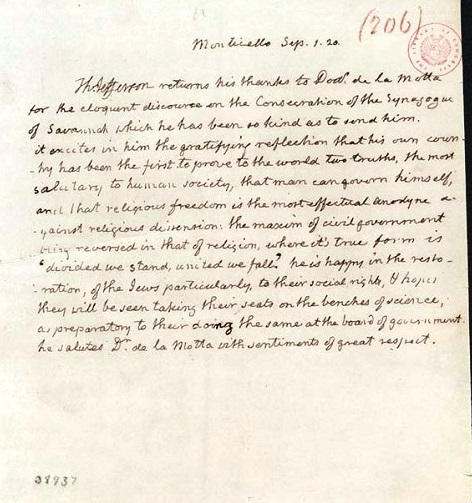

The third president used the phrase in a letter he wrote to Jacob de la Motta, an American physician, Army veteran, and Jewish communal leader, who had sent Jefferson a copy of his remarks at the dedication of Congregation Mickve Israel, a synagogue in Savannah, Ga. In his reply , written at Monticello on September 1, 1820, Jefferson described how “gratifying” he found it that the United States was the first nation in history “to prove to the world two truths, the most salutary to human society — that man can govern himself, and that religious freedom is the most effectual anodyne against religious dissension: the maxim of civil government being reversed in that of religion, where its true form is ‘divided we stand, united we fall.’”

Jefferson’s point was not merely, like that of George Washington’s famous letter to the Jewish community of Newport, R.I., that the new American government was committed to religious tolerance, and would give “to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance.” He was arguing something deeper, and as relevant today as ever: The surest way of preventing a society from tearing itself apart in religious strife is not through the establishment of an official religion, but through a steadfast refusal to give any religious creed the endorsement of the state, let alone to dictate how Americans should worship or what faith they should confess.

Our most volatile clashes and controversies tend to flare up when government has its heavy hand on the scale. The never ending skirmishing — or worse — over what is to be taught in public schools is a good example. Because schools are controlled by the government, and the government is controlled by those with the most political power, parents, teachers, and administrators frequently find themselves at daggers drawn.

"Throughout American history," Neal McCluskey, a scholar at the Cato Institute, has written, "public schooling has produced political disputes, animosity, and sometimes even bloodshed between diverse people." Battles royal have erupted over race and ethnicity, over Darwinism-vs.-intelligent-design, over the censoring of books and the wearing of armbands, over multiculturalism and sex education.

Yet furious conflict over religion in this country is almost unheard-of — even though most Americans feel at least as strongly about their religion as they do about their kids’ education. American Catholics and Protestants don’t get into vicious catfights over the pope’s authority. Orthodox and Reform Jews don’t wage war over the proper content of the Sabbath prayerbook. Atheists and believers don’t erupt in bitter clashes over whether children should be taught to pray before going to sleep. Though religious differences run deep, religious animosity is pretty rare. Americans live peacefully with neighbors whose deepest religious convictions they oppose. Why?

Because, in Jefferson’s words, “religious freedom is the most effectual anodyne against religious dissension.” Our Constitution enshrines religious liberty. Americans decide for themselves what to believe and how to worship. Government plays no role in those decisions. Politicians have no power to determine the doctrines of any faith. Church and state are separate in America. That’s why religion flourishes, and why it has tended flourish so peaceably.

There have been occasional exceptions, some quite shameful. Religious minorities have at times faced despicable persecution — Mormons were massacred, Catholics tarred as disloyal, Jews barred from hotels and universities. America’s religious tolerance hasn’t been perfect.

But those are exceptions, and they don’t invalidate the general rule: Where religious liberty is secure, divided we stand. Nearly two centuries after Jefferson penned his letter to Dr. de la Motta, America is a nation of 300 million and the home to faiths and sects the Founders never heard of. When it comes to religion, we are further from unanimity than ever. And yet we live, by and large, in a land of religious amity — a country where kosher bakeries play Christmas music, and no one bats an eye. Hallelujah!